This has been a challenging semester for my students. I am teaching CISC108, the introductory class for Computer Science majors. The class is tough enough, even for many students with prior programming experience. But, due to the Global Pandemic, this Fall 2020 semester is online. In addition to my existing curricular framework, I have a lot of new course policies meant to make the experience easier: no exams, flexible deadlines, and a huge team of excellent TAs giving 12:1 attention. But even with all this, my students are all still struggling to stay engaged.

I decided, on Thursday October 29, that I wanted to mix things up a little for Halloween. It’s always been my favorite holiday, and I have historically gone overboard with costumes and decorations. But this year, I had something even more elaborate in mind for my students: an interactive adventure game experience. When students logged into Zoom lecture, they were met with my empty chair and instructions to complete the classwork assignment on Canvas.

Prerecorded videos guided them to write code in BlockPy and eventually help rescue from my patio. Nothing too terribly spooky, but I think it’s still fitting for the season. The video below captures the experience that my students had. In the following sections, I describe how I put the whole thing together in a single (long) night.

How I Did It

I got the idea for this assignment from Escape Rooms, where you lock participants into a room and have them solve puzzles to escape. Recently, a number of teachers have leveraged this idea for educational purposes, feeding into the idea of Augmented Reality for teaching. I have also always loved the aesthetic of Full-Motion Video games that were popular in the 90s. These all served as the inspiration for my little adventure game.

I pitched the idea to my household around 8pm on Thursday, knowing that I would have to work very quickly to have it ready by 10am the next day. As you can tell from the final video, I had a full cast helping me out; they were also crucial in the planning sessions. I was able to get the script banged out by 9pm, and finished recording all the videos out in my patio around 11pm. All of the raw footage was shot on my phone propped up against a wine bottle.

Post-processing was done using Microsoft’s Video Editor - I remember Windows Movie Maker being vastly superior, but this built-in program was suitable for my purposes. I also added a video filter by Nick John to give the footage a “VHS” effect. The end credits and some of the footage joining was done in PowerPoint (still one of my favorite animation programs). I hosted all the videos off YouTube, for simplicity sake.

All these videos were embedded within BlockPy, which is also what provided the interactivity. For those who are not familiar, BlockPy is a dual-block/text Python programming environment. Originally created for Data Science in our Computational Thinking class, BlockPy’s feature set has extended dramatically over the years. In particular, its autograder has spun off to become one of my biggest research projects: Pedal.

Pedal is a framework to analyze student’s code and provide feedback. Pedal is not only a collection of powerful program analysis tools, but is also built to give a model for what Feedback should be. We want to go beyond unit testing and runtime errors. Our goal is to elevate Feedback with Software Engineering and Instructional Design practices, to make it a central part of your course’s development rather than an afterthought.

Pedal is completely independent of BlockPy, and works on VPL, GradeScope, and any other autograding platform that let’s you run arbitrary Python code. However, BlockPy probably has the best native support, since that was its original home. In particular, its HTML feedback output is supported in BlockPy for full rendering. This is critical to let the system play videos.

Essentially, every time the student runs their code, it evaluates their answer with an Instructor Control Script. Each time, it decides how far along they are in completing the objectives, and provides an appropriate feedback message. Typically, this is a new Video, but in other cases it can be actual feedback on mistakes in their code. Boolean flags help keep track of their progress, but these are not persistent between runs; each time it is reanalyzing the entire student file.

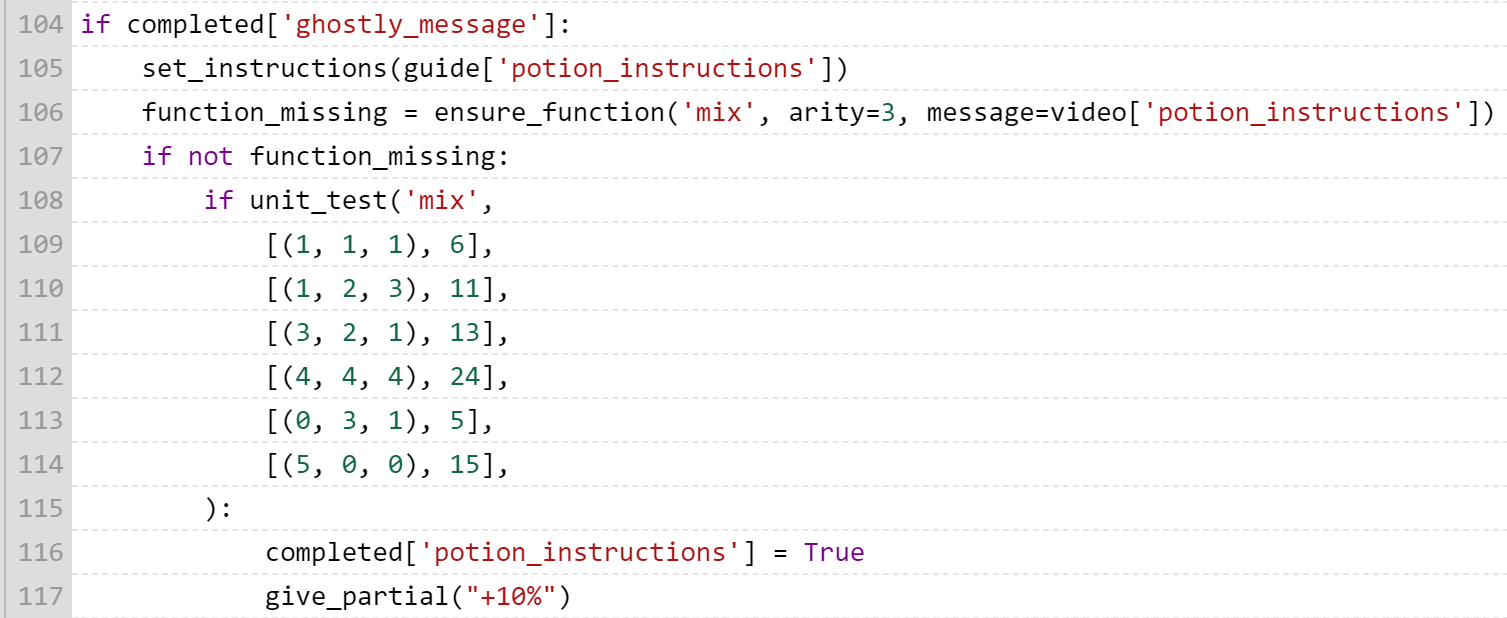

The code snippet below demonstrates some of the instructor control script logic.

If they’ve previously completed the “Ghostly Message” event, then they are shown instructions for defining the Potion Mixing function.

If they haven’t yet defined the mix function with three parameters, it shows the video for that scene (the video variable is simply a dictionary mapping symbol names to the YouTube embed codes).

If the function is defined, then it is unit tested (using Pedal’s very sophisticated unit_test function).

If everything checks out, we give them 10% of the assignment’s points and flag this phase as complete.

One of the smaller features I was particularly pleased with, that is not shown in the video above: creepily integrating the students’ name. At one point, students are asked to define a function, but the instructions are vague about what exactly to return. You’re more or less guaranteed to get it wrong the first attempt. When you do, the test case that it shows you failed will use the students’ own name. Since BlockPy is embedded into Canvas through LTI, we can access a little bit of student information. I don’t know if students noticed, but hopefully that was a little unnerving.

Student Reception

I finished all the coding around 3am, meaning the whole endeavor only took me about 7 hours from start to finish. Less than an hour later, one of my TAs tried the adventure and praised it. I hadn’t told them I was doing this, and they don’t usually remark on my assignments positively during the middle of the night, so I was pleased to have the spontaneous feedback.

We had a few hiccups in deployment.

I messed up the file-handling system so students apparently weren’t seeing my creepy "The door refuses to open" message, and I also temporarily borked up the ghost’s unicode.

However, none of these prevented the majority of my students from completing the game.

I’ve only had a few responses so far, but it seemed like most students were enjoying the experience. They sorted themselves into breakout rooms, and within those rooms I did observe students interacting (cameras were even on sometimes!). I’m looking forward to reviewing survey results and seeing whether it comes up in my end-of-semester evaluations.

I’m really pleased with how quickly the whole thing came together. The story is a little corny and the acting is over-the-top, but I don’t mind. I think the model is something I could replicate again in the future, although I do feel that an important element is the last-minute deadline and the holiday inspiration. I doubt I could put together an entire semester of such activities, nor do I think they would necessarily be welcomed. Still, I love integrating game-like experiences into my courses. There’s still a little part of me that never really outgrew wanting to be a game designer. Of course, now I think I’ve found something even better - curriculum developer :)