It’s been about half a year since I last posted, because it’s been a busy time creating new tools and curricula. Also in the past semester, I taught the “Introduction to Computer Science” course for CS majors (CISC108) for the third time. Recently, I was allowed to switch the course from Racket to Python. There’s a lot to go into about that change another time, but for this blog post I wanted to focus on a particular curricular design decision: using optional static typing in Python.

For those not aware, Python has supported type annotations since version 3.6, although the language itself doesn’t do much more than parse them. However, if you use the right tools, then you can get some advantages by writing code like this:

def repeat(message: str, times: int) -> str:

return message * times

greeting : str = "Hello world!"

repeat(greeting, 5)

Overall Consideration

I requested peoples’ experiences using the static typing on the SIGCSE-Members listserver. I would briefly summarize the responses as “nice and helpful, although not necessarily a game changer overall”. Now that I’ve taught with static type hints, I agree with that summary.

Overall, I really liked the conversations it afforded me with the students and how it made the conversation about types more concrete. There was a barrier for students as they learned the syntax and sometimes they would confuse things like a parameter’s name and the parameter’s type. However, it seemed like it gave them a concrete handle to build around, sometimes. I definitely intend to keep using type hints.

Despite the vast trove of log data that I collected this semester, I doubt I could answer a question like “did static typing help students learn big idea X better than not using typing?”. I will probably be able to answer some questions about how students used types, places where students struggled with types, and identify lingering misconceptions students had about types. But my instructor intuition is that it was a good thing.

Static Typing in My Course

As I mentioned before, the standard Python language specification doesn’t say much about type annotations. They are stored in the AST of the parsed code, and some information is made available at runtime. From there, tools like MyPy are expected to pick up the slack and give richer information to IDEs. The built-in typing module does offer an expressive type system that lets you capture more complicated constructions. But there is no actual requirement for how type annotations should look, the way there is in Java. The only real requirement is that type annotations are syntactically valid code that can be safely evaluated at runtime (e.g., you cannot use a variable that has not been previously defined).

A little freedom is a dangerous thing for an instructor. I decided that I did not want to be bound by using the typing module due to its increased complexity - my goal for the past semester was to have minimal impact on the existing curriculum. Therefore, I did make some pedagogical design decisions that might be a little controversial, since they are not authentic professional practice. However, I think that they have some merit and are worth discussing.

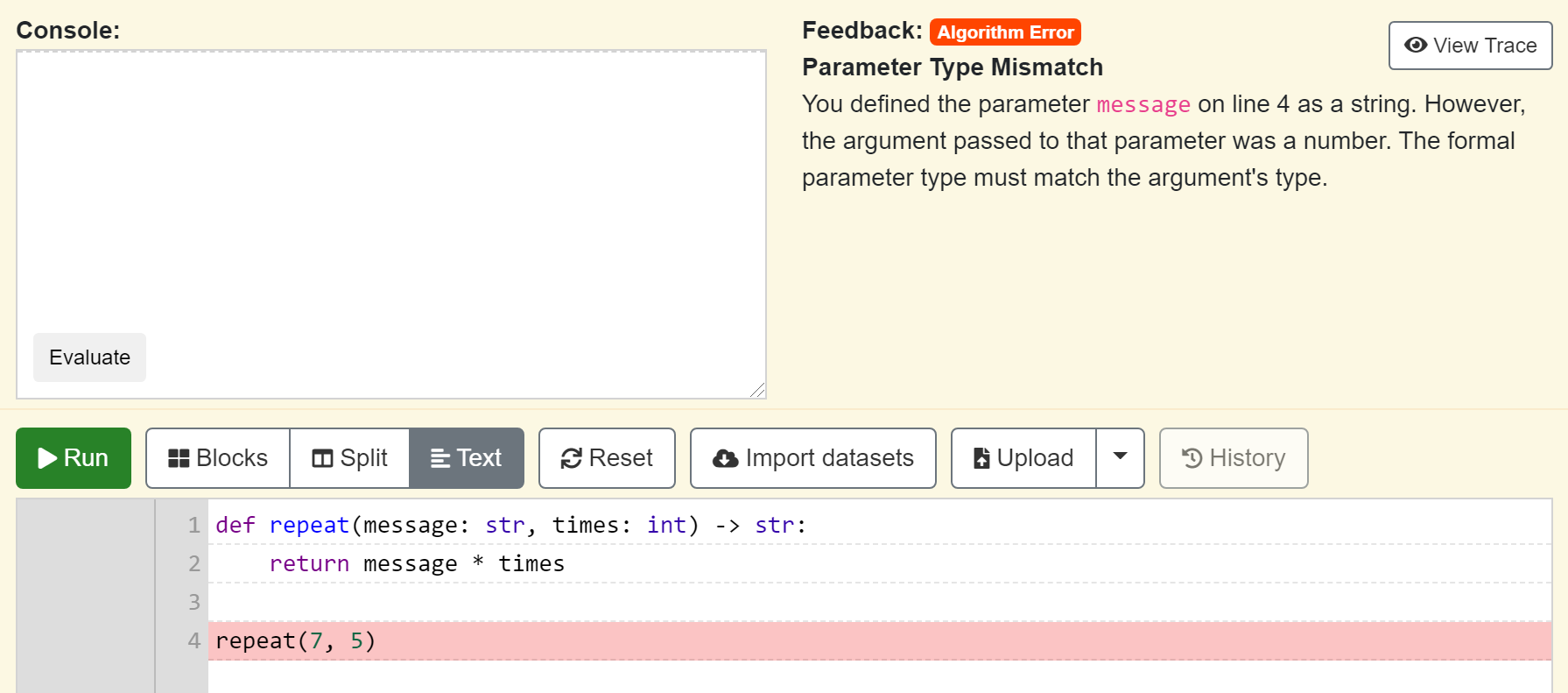

In my CISC108 course, students move from BlockPy to Thonny. The latter is an awesome educational desktop environment, although it doesn’t currently have any integration with a typechecker (or at least, it isn’t activated by default). BlockPy, on the other hand, is my own project and I like adding stuff to it. In particular, I added new tools to Pedal, our autograding/feedback architecture, that allow me to give feedback on students’ code in terms of type annotations.

I only used type annotations for function signatures, not regular variables. Pedal’s static analyzer actually already type checked all functions and operations, so this was not really that big a change. However, I added new checks to existing questions that forced students to statically type their functions correctly. Further, the final project (where they created a game in Arcade) required them to explicitly detail the exact type of their game’s model (their “World”), and the system would constantly verify that they had not strayed from that type. During exams, I did not require static types, but otherwise all other assignments required static types.

Type Hinting Simple Data

My PythonSneks curriculum focuses on simple types early on: int, float, bool, str, and None. Ignoring the latter, these were basically the same as the example given earlier. Here’s the signature of a predicate function:

def check_has_number(text: str, number: int) -> bool:

pass

This would indicate the check_has_number function consumes a string and an integer, and produces a boolean.

Type Hinting Lists

The first major divergence from regular Python typing was with Lists. I think this actually worked out very well. Here is how you would conventionally typecheck a function that consumes a list of integers:

# Conventional typechecker

from typing import List

def summate(numbers: List[int]) -> int:

...

However, instead I had students use the following style, which I found much simpler:

# My version

def summate(numbers: [int]) -> int:

...

In other words, you create a list literal with the element type inside. You could also use the generic list type, but I have a conversation with students about how that’s less precise.

This approach avoids an import and a confusing conversation about “list” vs. “List”. I was actually inspired by a mistake that almost 1/3 of my students used to make: when I told them to define a function that consumes a list, that non-trivial percentage of students would include square brackets around the parameter name. Well, this gives them an outlet for that desire.

Type Hinting Dictionaries

Now, here’s where things will get a little controversial. I wanted students to be able to specify types for a struct-like thing. Historically, I have taught dictionaries as a record/struct/fixed-sized heterogenous data container (among other uses). I explored a few other choices this semester, including regular classes, data classes, and namedtuples. However, I ended up settling on the following syntax:

# My style

Dog = {

"Name": str,

"Age": int,

"Is fluffy?": bool

}

def get_age(a_dog: Dog) -> int:

return a_dog['Age'] * 7

ada = {"Name": "Ada", "Age": 2, "Is fluffy?": True}

print(get_age(ada))

This was inspired by the new TypeDict PEP 589 that’s been accepted. The feedback system would quite strictly ensure that all keys were present the dictionary, that there were no unnecessary keys, and that the keys’ values were the correct type. This is obviously more complicated than the List type hints, since now there’s the potential misconception from the instance (a_dog) and the type (Dog).

I don’t think it was a failure. Although there was some struggle, many students seemed to pick up the idea. The lessons around them were later in the course and somewhat rushed, so I think there’s a huge room for improvement if I decide I want to stick with the dictionary literal style. Their final project had some type checking for defining a Game World, and the added support from the typechecking made a HUGE difference in the errors they got. I really loved that part.

I made the choice in syntax very close to the assignments’ release date, because I had time deciding how things should look. I almost went with the following style instead:

# Alternate style considered

class Dog:

name: str

age: int

is_fluffy: bool

def get_age(a_dog: Dog) -> int:

return a_dog['Age'] * 7

ada = {"Name": "Ada", "Age": 2, "Is fluffy?": True}

print(get_age(ada))

However, I shied away from having to teach the class keyword and potentially misleading them about a much more complex topic. Although my style is completely unconventional, any damage it causes is at least limited to just dictionaries. I want to experiment some more with what a reasonable type definition for structured data should look like. I’m still very drawn to the class style, but I wanted to see if other people had feelings about the dictionary style.

Type Hinting Union Types

I strongly considered teaching the following, but ended up chickening out.

Bear : str = {"Polar", "Black", "Brown"}

def is_dangerous(a_bear: Bear) -> bool:

...

is_dangerous("Polar") # Valid

is_dangerous("Koala") # Error!

This is heavily inspired by the typing style endorsed by the How-to-design-programs curriculum. They would say “A Bear is a string, one of either ‘Polar’, ‘Black’, or ‘Brown’.” Essentially, enumerations and itemizations. Ultimately, I decided against this since it didn’t add a whole lot but required additional lessons - I was already changing too much this semester.

What Do You Think?

Ultimately, I wrote this blog post to record, publicize, and raise discussion about how I taught Python types this semester. I’m not sure I made the right decision in straying so far from the official Python typing approach. Based on my teaching evaluations and my assessments, I think things mostly went well this semester. But it’s almost impossible in education to say that this was the best outcome.

My reference materials for the type information had several paragraphs explaining why I made up a custom type system. I doubt most students read it, but I do have fears of my students getting an internship and looking silly when they start statically typing in my weird made-up style. I try to avoid teaching unconventional concepts or made-up stuff. Not that I try and only teach authentic topics, but I try not to actively lie. Does this count?

This is an example of a case where I felt it would be worth bending the existing language to better suit my pedagogical needs. Was it the right choice? I don’t know, I am still tempted to teach a different style in the future. Particularly if I was using an IDE like PyCharm that auto-completes the type information and provides rich, immediate feedback.

If you have opinions/thoughts/suggestions/criticisms, I hope you’ll write your own post!