Pedagogy

This section covers the course topics, schedule, organization, and components of the course.

Topics

By the end of the course, students should be able to:

-

Create simple programs that solve problems using Python.

-

Interpret and debug a Python program using debugging techniques.

-

Describe, identify, and use core language elements of the Python programming language.

-

Represent data using simple and complex types to perform basic data processing.

-

Trace and code nonlinear control flow in a program using loops and conditionals.

-

Organize code using functional and object-oriented programming strategies.

-

Determine when a problem is solvable using computational techniques.

-

Summarize, criticize, and participate in computing culture and history

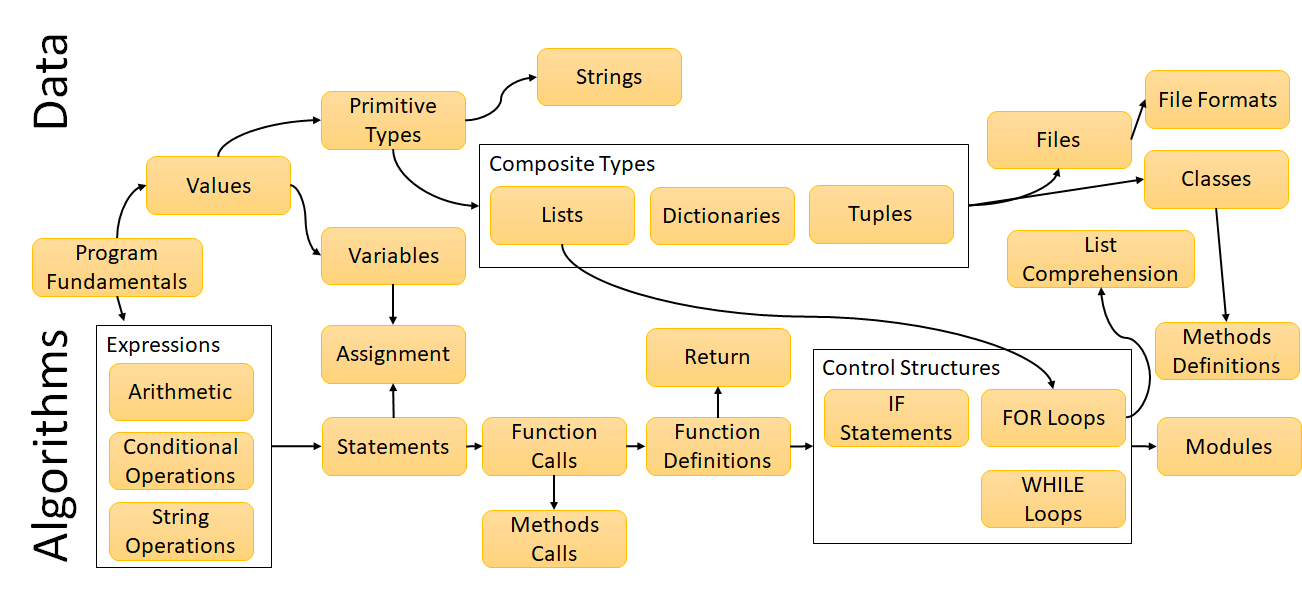

There are two paths of topics in this course: data and algorithms. These paths criss-cross over the course of the semester, but their general progression is shown in the figure below:

On the *data *side, students build up progressively more complex ways to represent values: first as primitive values, then using various composite types (homogenous lists, heterogenous dictionaries), and finally externalizing data into files. Through it all, they need to understand that Python is oriented around data, rather than variables - values have types, and variables have values, but variables do not have fixed types.

On the *algorithms *side, students learn progressively more complicated forms of control flow. First, they get a basic model of sequential execution. Then they see how functions disrupt that flow (and the impact this has on the flow data within the program). Next, they learn branching (IF statements) and loops (FOR loops and WHILE loops). WHILE loops are de-emphasized compared to FOR loops, because they are a less safe form of iteration (and are generally de-emphasized in the language). If you are used to other programming languages, you should become prepared to stop using WHILE loops in favor of the vastly superior FOR loops.

Students learn these topics, but apply them at various levels. On the one hand, they will need to know terminology and use it to communicate ideas. They also need to have a conceptual understanding of the way features in Python work - these are “big ideas” like scope rules, how data flows in a program, and variable naming rules. Most importantly, however, is knowing how to read and write actual code. Writing programs that solve specific and ill-structured tasks, at varying levels of size, is critical to programming.

The last topic shown in the syllabus is to summarize and participate in computing culture and history. Although not necessarily covered at the same level as other course concepts, it is important for students to learn that computing does not occur in a vacuum. Decisions were made by humans about the design and features of the Python language, and software continues to grow and change based on the motivations of the community. Students need to stop treating computing as an external force to be studied, and instead see it as a community to be joined and affected.

Schedule

The course is organized into weekly modules. Each module has multiple lessons, each of which has a number of assignments associated with them.

-

Getting Started: A gentle orientation to the basic ideas of a program, plus the format of the course, help-seeking behavior, and how to be an effective learner.

-

Basics and Primitives: Basic ideas of types, values, arithmetic and logical operators, sequential execution, variables, and assignment statements.

-

Strings and Calling Functions: How built-in functions and methods can be used, and the ideas of using and manipulating string data.

-

Making Functions: The basics of defining a function, and how this affects control flow.

-

Using Functions: More ideas of how to pass around data and information with functions.

-

Ifs and Lists: Using if statements and operations on lists.

-

For Loops: Processing lists of data using FOR loops, and applying common iteration patterns (summing, mapping, filtering).

-

More Looping: Important differences between strings and lists, basic idea of WHILE loops (and why we don’t use them much).

-

Dictionaries: Using dictionaries and the differences between dictionaries and lists

-

Data Structures: creating complex data representations by nesting dictionaries and lists, also a bit about tuples and multiple assignment.

-

Files: Accessing data in files and online, both as flat text files and in JSON format.

-

Data Science: Making plots, using Jupyter notebooks, and conducting data science investigations.

-

Project and Review: Time devoted in class to completing the final project and trying the Review material.

-

Project and Review: Time devoted in class to completing the final project and trying the Review material.

-

Conclusion: Final exam, final surveys, and final words.

Lesson Format

A typical lesson in this course is composed of 2-3 parts of web-based material:

Video Presentation

A recorded lecture that covers all the material that students will be assessed on. These videos are meant to be short (around 2-4 minutes in length) and quickly convey the important material. These videos have transcripts, closed captioning, and the PowerPoints that they were generated from all available. Some students may also be familiar enough with the content to not need the videos; students who want to attempt the problems without reference to the videos or transcripts should not be penalized. However, they should be quickly referred back to the videos if they have not already taken advantage of them.

Optional readings are also available for most of the lessons, although it should be noted that students don’t seem to take advantage of these. Nobody reads textbooks. In fact, much of the material does not have readings annotated - students either didn’t notice or didn’t seem to care.

Mastery Quiz

A combination of multiple choice, true/false, matching, and fill-in-the-blank questions; these quizzes are automatically graded. Students can use as many attempts as they need. The quizzes are typically 5 or so questions. These questions are meant to test students’ understanding of the material presented. Each question should have an obvious connection to a learning objective, but may be testing misconceptions related to that objective.

Programming Activity

Typically, this is an activity mediated through BlockPy. However, it sometimes has a different form (e.g,. Install some software, use Jupyter Notebooks). These are usually autograded.

Lectures

Each module covers multiple days of lecture, depending on the course schedule. Lessons are not 1-1 to lectures, and a given lecture may span multiple or only part of lessons. The in-class time for this course is not meant to be spent only lecturing. Instead, it should be a mixture of lecture, peer instruction questions, and time for students to work on problems with access to course staff.

Of course, pure didactic instruction is a useful tool for conveying information and reinforcing big ideas. Slides are available for the instructor that include notes, clicker questions, and ideas for worked examples. Some instructors may feel more or less comfortable with having a lot of lecture - however, the lecture is meant to be light.

In previous semesters, much of class time (half days on Monday/Wednesdays, all day on Friday) have been in-class lab time. The TAs and instructor roam the room and answer student questions. This has proven helpful in engaging students who would not normally come to office hours, despite needing help. This could also be an opportunity for paired programming type activities.

Activity Groups

There are six types of graded activities in this course:

-

Mastery Quizzes (25%): The aforementioned quizzes administered after each video lesson.

-

Programming Problems (25%) : The aforementioned programming assignments administered after most video lessons.

-

In-class Activities (10%): These activities are left to the discretion of the instructor. In general, I have used iClickers to ask students follow-up questions or to engage them with lecture. See the Micro-class activities later on.

-

Ethics Activities (5%): These short-form writing activities are meant to gauge students understanding of ethics, and is largely meant to fill a university requirement. These are described later on.

-

Projects (20%): A series of mini-projects of escalating size and points possible, culminating in a final project that has two weeks of class time devoted to it.

-

Exam (15%): The two-part final exam, described later.

A large portion of the course grade (50%) is dedicated to problems that follow a Mastery-learning model: students can repeatedly attempt the problems until they achieve success. The In-class activities are also meant to reward participation. On the other hand, the Ethics Activities and Exam are more performance-oriented; the latter because it is a summative assessment, and the former because of the high human costs involved in grading. The projects give students ample opportunity to test and develop their solutions, but are still somewhat summative by their nature.

Deadlines

A number of schemes are possible for organizing assignments. A flexible schedule was used in the most recent semester. All assignments for a module open up the friday before the week of that module’s classes. Those assignments will lock two weeks later. Assignments are due one week after the module unlocks, but there are no late penalties (the due dates are meant to be guides). Grades for non-automatic assignments will be returned two weeks after the lock date.

This flexible schedule has been popular in the past. However, students who abuse it to wait till the last minute tend to suffer. There is flexibility here for an instructor to adjust due dates as they see fit and try out other schedules to suit their tastes.

Assessments

To assess students’ mastery of the material, there are three activities meant to be summative assessments of their understanding. These are scheduled for the end of the semester, and considerable time and attention are spent preparing students to succeed at them.

A number of TAs suggested that students might perform better in the course if midterms were used. These could incentivize students to pay more attention to the material and actually learn it.

Final Exam

The final exam has two parts. The first part is a subset of the questions asked in the Mastery Quizzes. The quiz covers the entirety of the course content by administering a different random subset to each student, in such a way as to make sure that almost all questions are asked at least once to at least 50-60 students. Further, each student is receiving a different copy of the exam, which makes it more robust against cheating. The final exam is discussed more in the final chapter.

The second part is a subset of the programming questions delivered electronically. The quiz covers only a subset of the course, with questions chosen to balance difficulty and importance. There are many opportunities for partial credit on this exam.

Final Project

The final project is meant as an escalation of the other programming projects. It should be specifically designed to not be able to be completed in a single sitting. Ideally, it will require students to apply a majority of the skills they have developed in the course, while still allowing for some freedom of expression. The final project is discussed more in the final chapter.